Sentiment in Shakespeare: Comparing Plays

E 310D | Hinrichs

Acknowledgments

This project draws extensively on the procedures laid out in a tutorial by Peer Christensen.1

It is also very indebted to Julia Silge’s {tidytext} package.2

Setup

Here are the packages we need to load.

Define a ggplot2 theme

This is a housekeeping task… let’s define a graphic theme to use later in the visualization. It is called my_theme and we do this purely for aesthetic reasons.

You could do this whole project without my_theme, but then you would also have to omit the command + my_theme() at the end of each plot command.

my_theme <- function() {

theme_apa(legend.pos = "none") +

theme(panel.background = element_blank(),

plot.background =

element_rect(fill = "antiquewhite1"),

panel.border = element_blank(),

strip.background = element_blank(),

plot.margin = unit(c(.5, .5, .5, .5), "cm"),

text = element_text(family = "Times New Roman"),

plot.title = element_text(hjust = 0.5,

size = 19,

face = "plain"

),

plot.subtitle = element_text(hjust = 0.5,

size = 16,

face = "plain")

)

}Index of plays

shakespeare <-

gutenberg_works(author == "Shakespeare, William") %>%

mutate(title = tolower(title))

shakespeare %>%

select(title, gutenberg_id) %>%

as.data.frame() %>%

gt()| title | gutenberg_id |

|---|---|

| the complete works of william shakespeare | 100 |

| shakespeare's sonnets | 1041 |

| venus and adonis | 1045 |

| beautiful stories from shakespeare | 1430 |

| king henry vi, first part | 1500 |

| history of king henry the sixth, second part | 1501 |

| the history of king henry the sixth, third part | 1502 |

| the tragedy of king richard iii | 1503 |

| the comedy of errors | 1504 |

| the rape of lucrece | 1505 |

| the tragedy of titus andronicus | 1507 |

| the taming of the shrew | 1508 |

| the two gentlemen of verona | 1509 |

| love's labour's lost | 1510 |

| king john | 1511 |

| romeo and juliet | 1513 |

| the merchant of venice | 1515 |

| king henry iv, the first part | 1516 |

| the merry wives of windsor | 1517 |

| king henry iv, the second part | 1518 |

| much ado about nothing | 1519 |

| the life of king henry v | 1521 |

| julius caesar | 1522 |

| as you like it | 1523 |

| hamlet, prince of denmark | 1524 |

| the phoenix and the turtle | 1525 |

| twelfth night; or, what you will | 1526 |

| the history of troilus and cressida | 1528 |

| all's well that ends well | 1529 |

| measure for measure | 1530 |

| othello, the moor of venice | 1531 |

| the tragedy of king lear | 1532 |

| antony and cleopatra | 1534 |

| the tragedy of coriolanus | 1535 |

| the life of timon of athens | 1536 |

| pericles, prince of tyre | 1537 |

| cymbeline | 1538 |

| the winter's tale | 1539 |

| the tempest | 1540 |

| the life of henry the eighth | 1541 |

| a lover's complaint | 1543 |

| the passionate pilgrim | 1544 |

| a midsummer night's dream | 2242 |

| twelfth night | 2247 |

| richard ii | 2250 |

| henry iv, part 1 | 2251 |

| much ado about nothing | 2252 |

| henry v | 2253 |

| henry vi, part 1 | 2254 |

| henry vi, part 2 | 2255 |

| henry vi, part 3 | 2256 |

| richard iii | 2257 |

| henry viii | 2258 |

| coriolanus | 2259 |

| titus andronicus | 2260 |

| timon of athens | 2262 |

| macbeth | 2264 |

| hamlet | 2265 |

| king lear | 2266 |

| othello | 2267 |

| shakespeare's first folio | 2270 |

| the tragicall historie of hamlet, prince of denmarke the first ('bad') quarto | 9077 |

| the tragedie of hamlet, prince of denmark a study with the text of the folio of 1623 | 10606 |

| shakespeare's play of the merchant of venice arranged for representation at the princess's theatre, with historical and explanatory notes by charles kean, f.s.a. | 12578 |

| a fairy tale in two acts taken from shakespeare (1763) | 12842 |

| king henry the fifth arranged for representation at the princess's theatre | 22791 |

| the works of william shakespeare [cambridge edition] [vol. 1 of 9] introduction and publisher's advertising | 23041 |

| the tempest the works of william shakespeare [cambridge edition] [9 vols.] | 23042 |

| two gentlemen of verona the works of william shakespeare [cambridge edition] [9 vols.] | 23043 |

| the merry wives of windsor the works of william shakespeare [cambridge edition] [9 vols.] | 23044 |

| measure for measure the works of william shakespeare [cambridge edition] [9 vols.] | 23045 |

| the comedy of errors the works of william shakespeare [cambridge edition] [9 vols.] | 23046 |

| the new hudson shakespeare: julius cæsar | 28334 |

| twelfth night; or, what you will | 38901 |

| shakespeare's comedy of the tempest | 47518 |

| the works of william shakespeare [cambridge edition] [vol. 7 of 9] | 47715 |

| the works of william shakespeare [cambridge edition] [vol. 3 of 9] | 50559 |

Shortcut

To simplify things a little, I downloaded 12 plays from gutenberg.org by hand. In what follows, we’ll be loading the text from the project folder, i.e. from hard drive, not from the gutenberg API. Easier that way…

Load plays from files

- Define an ‘open’ function.

open_play <-

function(path){

nami <-

path %>%

str_split("/") %>%

unlist() %>%

.[-1] %>%

str_split(".txt") %>%

unlist() %>%

.[1] %>%

str_split("_") %>%

unlist()

ti <- nami[2]

g <- ifelse(nami[1] == "t",

"tragedy",

"comedy")

t <- readLines(path)

t <- t[((which(str_detect(t, "%>%"))+1):

length(t))]

play <- tibble(

text = t,

genre = g,

title = ti

)

play %>%

select(title, everything())

}- Loop the function over all items in the directory inventory list.

The following plays are now loaded:

| title | genre |

|---|---|

| Romeo and Juliet | tragedy |

| Othello | tragedy |

| Macbeth | tragedy |

| King Lear | tragedy |

| Hamlet, Prince of Denmark | tragedy |

| Cymbeline | tragedy |

| Twelfth Night; Or, What You Will | comedy |

| The Winter's Tale | comedy |

| The Merchant of Venice | comedy |

| Measure for Measure | comedy |

| As You Like It | comedy |

| A Midsummer Night's Dream | comedy |

Overview of the plays we have, and the number of lines for each play:

| title | n |

|---|---|

| A Midsummer Night's Dream | 3049 |

| As You Like It | 3693 |

| Cymbeline | 5014 |

| Hamlet, Prince of Denmark | 5533 |

| King Lear | 4274 |

| Macbeth | 2889 |

| Measure for Measure | 4457 |

| Othello | 5110 |

| Romeo and Juliet | 4405 |

| The Merchant of Venice | 3634 |

| The Winter's Tale | 4071 |

| Twelfth Night; Or, What You Will | 3631 |

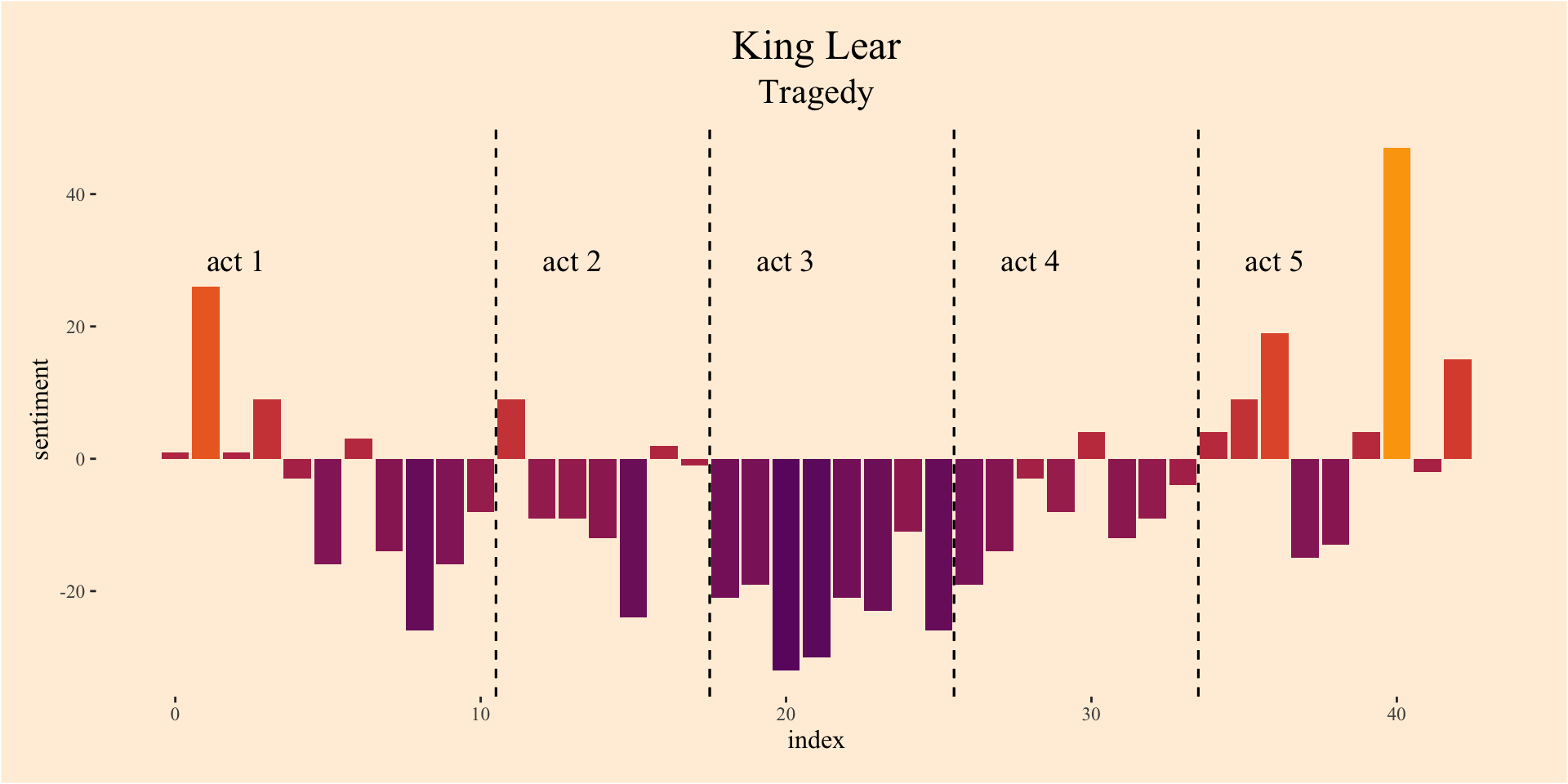

Write a ‘plot’ function.

plot_play <- function(mytitle){

acts <- plays %>%

filter(title == mytitle) %>%

mutate(line = row_number()) %>%

mutate(act = cumsum(str_detect(text, regex("^act |^actus ", ignore_case = T)))) %>%

unnest_tokens(word, text) %>%

inner_join(get_sentiments("bing")) %>%

count(act, index = line %/% 100, sentiment) %>%

mutate(new_act = act != shift(act,1)) %>%

spread(sentiment, n, fill = 0) %>%

mutate(sentiment = positive - negative) %>%

filter(new_act == T, act > 0) %>%

select(index, act)

sentiments2 <- plays %>%

filter(title == mytitle) %>%

mutate(line = row_number()) %>%

ungroup() %>%

unnest_tokens(word, text) %>%

inner_join(get_sentiments("bing")) %>%

count(index = line %/% 100, sentiment) %>%

spread(sentiment, n, fill = 0) %>%

mutate(sentiment = positive - negative)

sentiments2 %>%

ggplot(aes(index, sentiment, fill = sentiment)) +

geom_vline(data = acts[-1,],

aes(xintercept = index - 0.5),

linetype = "dashed") +

geom_col(show.legend = FALSE,position = "dodge") +

scale_fill_viridis_c(option = "B",

begin = 0.3,

end = 0.8) +

labs(title = mytitle) +

geom_vline(data = acts[-1,],

aes(xintercept = index - 0.5),

linetype = "dashed") +

annotate("text", x = acts$index + 2, y = 30,

label = paste0("act ", acts$act),

family = "Times New Roman",

size = 5)

}Test the function.

The function seems to work.

Visualize all 12 plays in the data

Hypothesis building

Omar

We are able to measure sentiment by looking at the charts. We are able to tell what genre it is by seeing whether the sentiment is negative or positive. The charts for comedies have a higher sentiment, and the charts for tragedy plays have a negative pattern in sentiment. Furthermore, being able to highlight keywords that is used by Shakespeare may be able to indicate if a play is a comedy or tragedy. In conclusion, positive sentiment is comedy, and negative sentiment is tragedy.

Leonardo

I believe simply subtracting the overall negative score from the overall positive sentiment score will give us a pretty accurate guess. Tragedies could be anything with an overall score of less than 10, and comedies be anything above 10.

Roy

We should teach it that a negative score means negative sentiment, and that negative sentiment correlates with a tragedy. A positive score correlates with positive sentiment, and that positive sentiment correlates with a comedy. It has to be noted though, that all of the plays do contain a mix of positive and negative sentiment, so the computer needs to take into account the whole of the play. It can either add up the positive and negative sentiments and take the greater value to define the genre of the play or it can take the overall sentiment per act and decide the genre of the play by whether there’s a greater number of positive acts or negative acts.

Scott

From the examples shown demonstrated that the more negative pattern in sentiment correlates to tragedy while positive correlated more to a comedy. The examples provided differed in how obvious the negative or positive attitudes were. An approach could be to search for phrases with certain words. One way to identify if a play is a tragedy or a comedy is to highlight specific terms that Shakespeare frequently uses in his tragedies or comedies, and this could potentially give us a direct answer on whether the play is a comedy or tragedy.

Thomas

First, we can measure a specific sentiment score (like an average sentiment or a sentiment distribution) for each play using an analysis tool and manually label each play as a tragedy or a comedy. Examining the correlation or relationship between the sentiment scores and the labeled genre, a computer learning model can learn how to recognize the differences between a tragedy and a comedy. T-test analysis could be helpful here. After evaluating the model’s accuracy, we can determine if sentiment score analysis can be a predictive feature for guessing the genre of a Shakespeare play.

Mary

From looking at the charts we can easily observe that comedies contain more positive sentiments, and tragedies contain more negative sentiments. Taking is into account it is safe to assume that you can determine the genre of the play based on whether it leans positive or negative when analyzing sentiments. With positive being comedy, and negative being tragedy respectively.

Cat

The examples shown varied in how clear their negative or positive sentiments were, so I believe if we were to be able to directly compare the number of positive words to negative words, the computer we’re training might be able to give us percentages and determine whther it is a comedy or a tragedy. Another way might be to look for not only words, but phrasing and context. Highlighting certain words that Shakespere commonly uses in his tragedies or comedies can be flagged as an indicator for a play’s designation as a comedy or a tragedy.

Kelly

From looking at the charts, we might be able to automatically measure sentiment, whether it is less or more, to figure out the genre. The charts for the tragedy plays seem to have more of a negative pattern in sentiment throughout the acts, whereas comedies have more of a higher sentiment throughout the acts.